The work is licensed under

a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License.

2023-03-23

The work is licensed under

a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International

License.

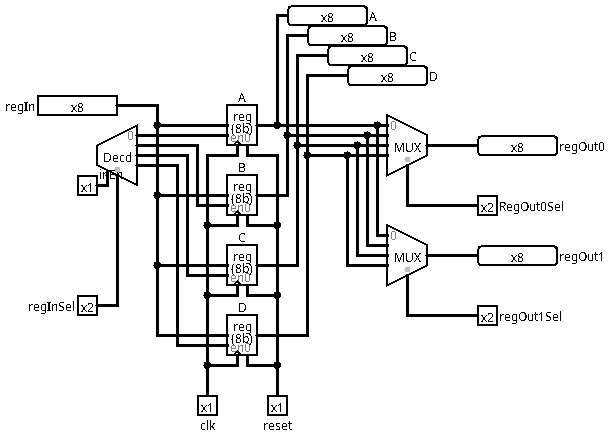

The register bank (sub-circuit regBank) houses four

software addressable registers. This means these four

registers, labeled register A to register D in TTPASM, can be specified

explicitly in opcodes. The register bank can update one of the four

registers, and connect up to two of the registers to the output of the

register bank.

Look into the regBank circuit, and understand how it

operates. Specifically, figure out the following:

regBank. There are two outputs.ALU

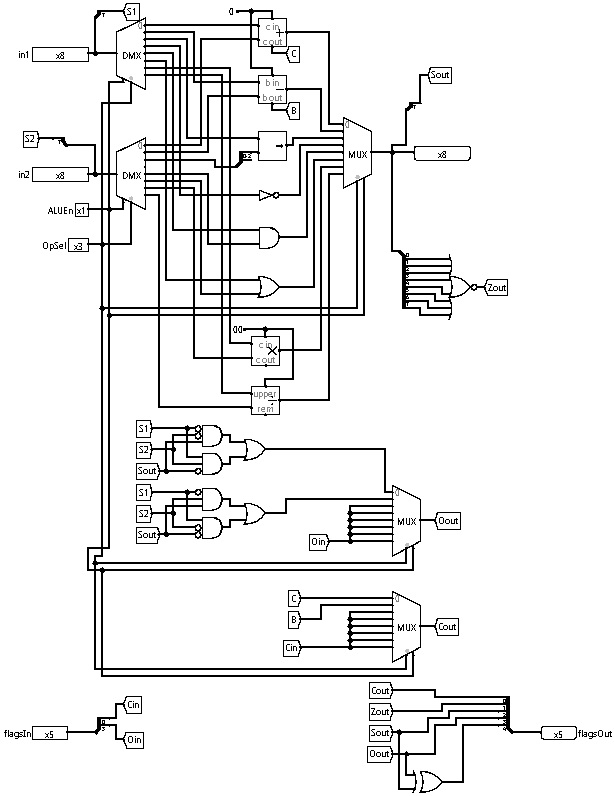

The ALU (arithmetic and logic unit) is responsible for

computations and “logic.” Logic, in this case, is merely determining

some elementary conditions, such as whether the minuend is less than the

subtrahend in a subtraction, or whether the result of an operation is

zero.

The ALU itself does not provide values to computations,

nor does it store the results of computations. In TTP, registers are

used to supply data for computations, as well as to store results of

computations.

In the circuit of the ALU, there are many multiplexers

and demultiplexers to route values needed for computations and results

from computations. Track down how this routing is specified by the input

pins of the ALU. Furthermore, track down the outputs of the

ALU, and backtrack to figure out what each output

represents. This is particularly important for the bits related to

flagsIn and flagsOut.

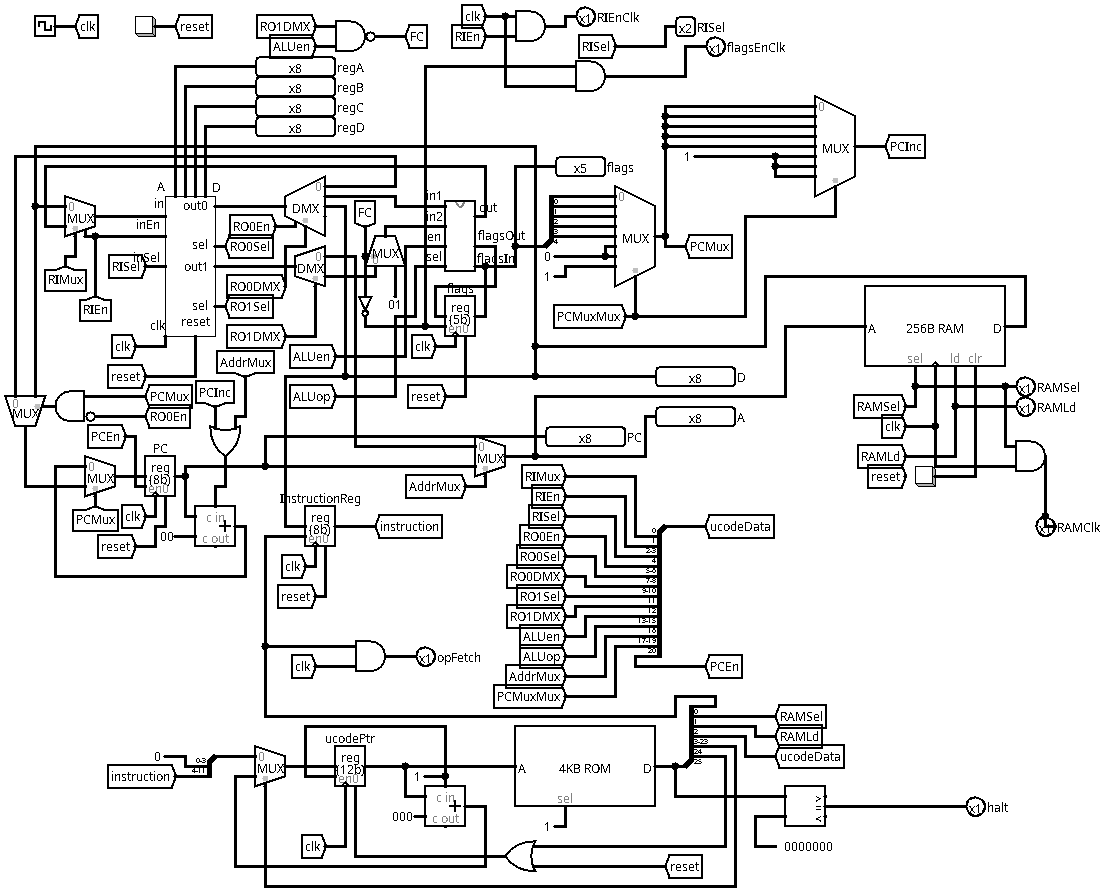

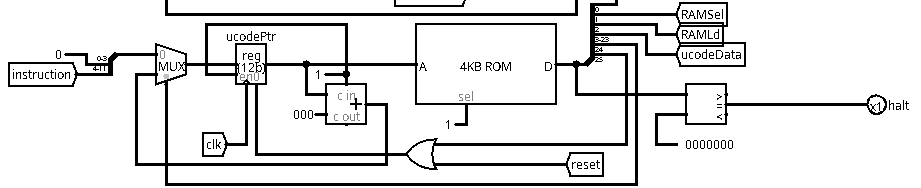

The controller is the lower portion in the TTP, centering around the only ROM component.

The controller is responsible for the coordination of all the other parts of TTP to perform actual operations.

Technically, the RAM component is not a part of TTP. In reality, RAM is often outside of the die of a processor because it takes up more spaces. However, the are processor chips that include RAM when the amount of RAM can be combined to the same die.

RAM is used to store/supply opcodes, this is the main idea of a von Neumann architecture. However, RAM is also used to store global variables, as well as the stack.

TTP has a few registers that are not software addressable. This means that these registers cannot be directly accessed by opcodes.

ucodePtr: the microcode pointer is a register that

connects to the ROM component. This register is at the core of

controller part of TTP. Of all the registers, ucodePtr is

the only one that is sensitive to a falling edge instead of a rising

edge.PC: the program counter stores the address in RAM (not

ROM) of where to find the next opcode.flags: the flags register stores the carry, zero,

overflow, sign, and less-than flags from the ALU from the most recent

ALU operation. These flags can, then, be utilized by conditional branch

instructions.InstructionReg: the instruction register temporarily

stores a copy of the opcode in RAM that is pointed to by

PC, which is then used to update ucodePtr to

“decode” an opcode.At first glance, TTP looks like a big mess with wires and tunnels everywhere. However, there is a structure method to gain an understanding of how it gets work done.

When ucodePtr==0 on a rising edge,

InstructionReg=*PC, and this is called the fetch

cycle/phase of executing an opcode. You may want to examine location 0

of the ROM, and see how registers are enabled, how RAM is enabled, and

how multiplexers and demultiplexers are configured to accomplish the RTL

(register transfer language) description

InstructionReg=*PC.

Sort of part of the fetch cycle, when

ucodePtr==1 on a rising edge, PC=PC+1 to

autoincrement the program counter for the next opcode. Again, it is

useful to understand how the D port of ROM controls a multiplexer to

specify this behavior.

When ucodePtr==1 on a falling edge,

ucodePtr=InstructionReg << 4. Track down the circuit

to find out how this is accomplished by a splitter, a multiplexer, and

the corresponding bits from the D port of ROM.

After decode, ucodePtr points to a specific location in

ROM. The content at this location of ROM is presented to the D port of

ROM.

There is no easy way to describe what happens in the execute

cycle/phase of executing an opcode because this part depends on the

opcode. The ROM allocates 16 microcode slices (locations in ROM) per

opcode. However, most opcodes can be accomplished by two microcode

slices. Every opcode needs the last microcode slice to reset

ucodePtr to zero.

To analyze a specific microcode slice of a specific opcode:

regBank, ALU,

PC, RAM. These components have specific ports

that can help indicate whether they are in use or not.In simpler terms, to understand what a microcode slice does, first determine the active components used, then find out how these components are routed to each other.